What Starbucks can teach us about software scalability

In 2004, Gregor Hohpe published his brilliant post “Starbucks Does Not Use Two-Phase Commit.” When I read it, my time working at Starbucks during my college years suddenly became relevant. Over the years, I gradually realized there’s even more that programmers can learn from the popular coffee chain.

Although many people may want to build scalable software, it can be much harder than it first appears. As we work on individual tasks, we can fall into a trap, believing all things are equally important, need the same resources, and happen synchronously in a predefined order.

It turns out they don’t—at least not in scalable systems, and certainly not at Starbucks.

🔗How to make coffee

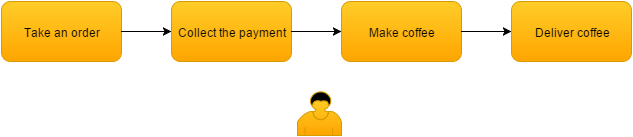

Preparing coffee at Starbucks is a four-step process. First, customers stand in line (a queue) at the counter and place their orders, following the first-in-first-served rule. Second, the employee (barista) takes an order from the customer and accepts the payment. Third, they start preparing the drink. Fourth, when it’s ready, they place the drink on the counter and call out the customer’s name.

Although this may sound like a reasonable model, it can quickly lead to long lines. It’s impossible for one person to do more than one thing at a time, so customers start queuing up while the barista works through each order sequentially. If they want to serve more customers, they need to scale. Let’s look at ways they can do that.

🔗Scaling baristas

One way Starbucks can scale is to hire super baristas—very talented, fast-working, bright people. They’d need to invest heavily in their development, optimize every aspect of their work, and constantly improve their efficiency. In software, such an approach would be called scaling up (vertical scaling).

The problem with the scaling up strategy is that there’s a limit to how fast (and how long) one person can work. At some point, even the super barista won’t be able to meet the demand. When this happens, customers will leave the shop frustrated and may not come back.

Similarly, there’s a limit to how far we can optimize our software if everything runs sequentially. We just can’t buy a 200GHz CPU. Even the biggest CPUs are multi-core, with each core clocking at no more than 3–4GHz.

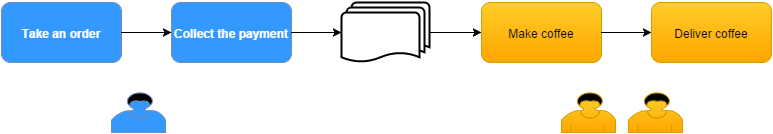

Another way Starbucks can scale is to organize the work in a way that allows adding more normal workers, which is the essence of concurrent processing in software. After one barista takes an order, another can start preparing it. The first barista can then take another order while the first order is prepared in parallel.

You might think that the best idea would be to consider concurrent processing only after the demand reaches a certain level. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. There’s no magical switch that will allow us to turn on concurrency just when we need it. We need to prepare in advance.

Starbucks knows that. When a new store opens, even if they have only one employee per shift, everything needed for concurrency is in place from day one. They are ready to add more people at any time.

Lesson learned: We can’t apply concurrent processing easily if we don’t build our system in a way that supports it.

Now let’s look at how Starbucks accomplishes this.

🔗It starts with messaging

If you’ve ever ordered coffee at Starbucks, you might have noticed little boxes on the cup filled with symbols. These symbols are a sort of shorthand used by the baristas to quickly identify the drink as well as any extras (e.g., whipped cream, foam, etc.).

The cup, or message, is essential for communication between employees. It signals to the barista that a beverage needs to be created and the symbols written on it provide details on what kind of beverage to prepare. Even if the coffee shop isn’t busy and there’s only one person servicing customers up front, they will still add symbols to the cup.

At first glance, this might seem like extra work. But if a large group of customers suddenly enters the shop, the other employees from the back can immediately jump in to help. Without the need for any additional communication overhead, they can start making drinks based on the messages.

Lesson learned: Sudden spikes aren’t problematic if we can easily add more workers anytime and divide the work among them. Using messages is one way to do that.

🔗Divide and conquer

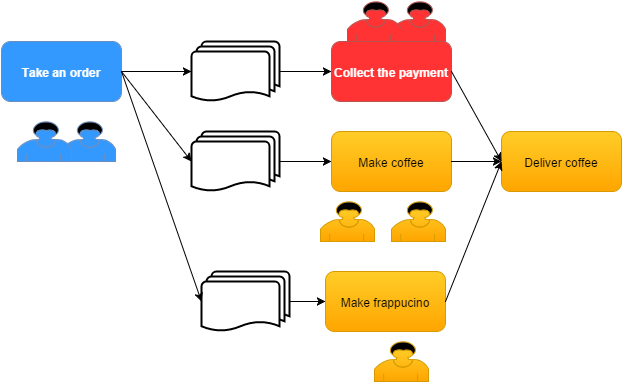

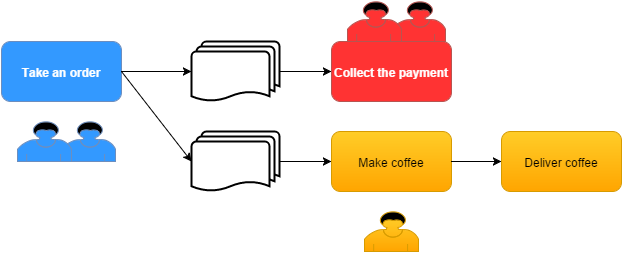

As described earlier, the whole coffee making process can be covered by a single employee—a barista. But the default setup at Starbucks is to have one employee (a cashier) taking orders and payments and another (a barista) making drinks.

Usually, the slowest part of the process is preparing coffee, which is why multiple baristas prepare drinks when the shop gets busy. Often they’ll take cups from the same pile and share the work evenly. This is an example of the Competing Consumers pattern.

There can be scenarios, however, in which this approach runs into trouble. Let’s say there are three baristas working with one coffee machine and one Frappuccino machine. Three customers order a coffee and the next one orders a Frappuccino. The person taking orders queues up four cups with the appropriate symbols on each. Each barista grabs a cup to make coffee. The first one starts making their drink and the other two are now blocked waiting for the coffee machine.

We can avoid this contention for resources by dividing up the work. One way to do this is to separate messages into more fine-grained types so that they can be handled differently. For example, we’ve seen how Starbucks uses the cup as a message to indicate that a drink needs to be prepared. But the system also differentiates between hot and cold drinks: hot drinks are served in paper cups and cold ones in plastic cups. When we receive three orders for hot coffee followed by one for a Frappuccino, we now have three paper cups and one plastic one in two different piles. The first barista grabs the paper cup from the first pile and starts preparing the drink. The second barista, seeing the coffee machine is busy, grabs the plastic cup from the second pile and uses the Frappuccino machine instead. Now we have drinks from both piles being prepared in parallel.

This kind of work division, in which baristas divide tasks and work in parallel, is called partitioning.

Lesson learned: It turns out partitioning is a crucial element of an effective scaling strategy. Not all work needs the same level of scaling. Small tasks that are done fast can be done by a single worker while multiple workers take care of the more demanding, slower tasks. By using partitioning, we can scale each activity independently.

🔗Not all work is equally important

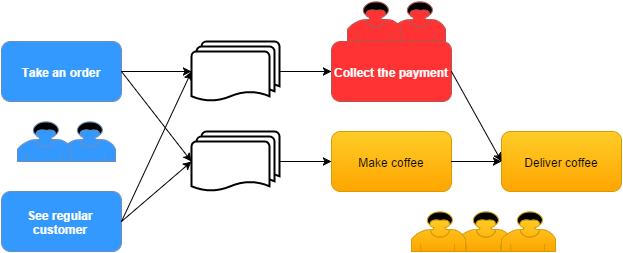

One of the things that makes Starbucks successful is that they’ve trained their staff in the importance of recognizing the regulars. Take the guy who comes in every morning to get two venti americanos and two grande lattes to bring his team. Or the woman who every Wednesday orders a tall caramel macchiato and then stays in the shop for an hour to read her book.

If a barista notices the “tall caramel macchiato woman” entering the shop on Wednesday, they will start preparing her favorite drink even before she comes to the counter. The customer gets a pleasant surprise when she never has to say what she wants. The cashier already knows her usual drink, so they only ask her how she’s doing and take the payment. Before the payment is completed, her coffee is already waiting for her at the counter.

You might be surprised how high a percentage of Starbucks’ customers are regulars. Giving them the best possible experience is a high priority. Quite often, they end up getting their drinks faster than other customers. This makes them feel important and encourages them to come back, thus increasing their value to the company.

Lesson learned: Some tasks are more important than others. By organizing standard activities into reusable, independent building blocks, we can easily modify the process to provide superior service for the more valuable tasks when the need arises.

🔗Not all mistakes are worth preventing

In all the examples above, Starbucks employees needed to verify that customers paid before receiving their coffee. To make sure that happens, baristas could ask customers to show their receipts before handing over a drink. But that’s not how it actually works.

What Starbucks discovered is that very few people try to get coffee without paying. Their analysis showed it’s more profitable to keep baristas focused on fulfilling orders instead of preventing the occasional lost coffee. If someone happened to take the coffee you ordered (which usually only happens by mistake), the barista would prepare a new one for you, no questions asked.

Lesson learned: To build scalable systems, we need to embrace the idea that some failures are inevitable. It’s too expensive to try to prevent them completely. Instead we should focus on making sure we can detect issues quickly and compensate for them when they arise.

🔗Summary

What looked like a simple four-step process for making coffee evolved into an interesting business process. What seemed exceptional and rare at first glance turned out to be an essential aspect of the business.

Things like sudden spikes in demand or failures can happen multiple times per day. Designing a system that handles them well requires questioning common assumptions. Often the first model that comes to mind won’t address such concerns. Also, there are many more exceptional situations to consider. For example, cancelling orders is an interesting problem all on its own.

As the example of Starbucks shows, if we followed a naïve approach, our business would not be able to expand to serve a larger number of customers. Our service level would drop as we got more and more customers, to the point where they would stop coming. Instead, we need to organize our work in such a way that we can meet increasing demand. In the end, building systems that scale is just as much about rethinking our business processes as it is about technology.

For more information about how to build scalable software, check out the following resources:

- Scaling with asynchronous messaging

- Saga patterns derived from fast food examples

- Dish washing and the chain of responsibility

About the author: Weronika Łabaj is a developer at Particular Software. She is passionate about providing business value with software, exploring new paradigms, and challenging the obvious. At Starbucks, she always goes for a tall caramel macchiato.

Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter